BATON ROUGE, La. — It’s the start of brown shrimp season in Louisiana, and instead of a fleet of boats heading out to trawl nearby waters, fishermen have gathered like an armada at the Louisiana State Capitol to tell lawmakers that the industry is in dire straits.

Hundreds of longtime shrimpers tied up their boats and held a rally at the Capitol in recent weeks in a rare show of unity from all factions of the volatile shrimping industry. Shrimpers, dock owners, and processors have for decades pointed fingers at each other for driving prices down. But now, they’re all protesting against the unwanted competition affecting their livelihoods: imported shrimp.

READ MORE: For fishermen in Louisiana, a livelihood lost after Hurricane Ida

“It is to the point where we are about to lose our industry,” Acy Cooper, president of the Louisiana Shrimpers Association, told the crowd gathered for the May 12 rally. “We just had the opening of the season, and people are going into the hole trying to make a living.”

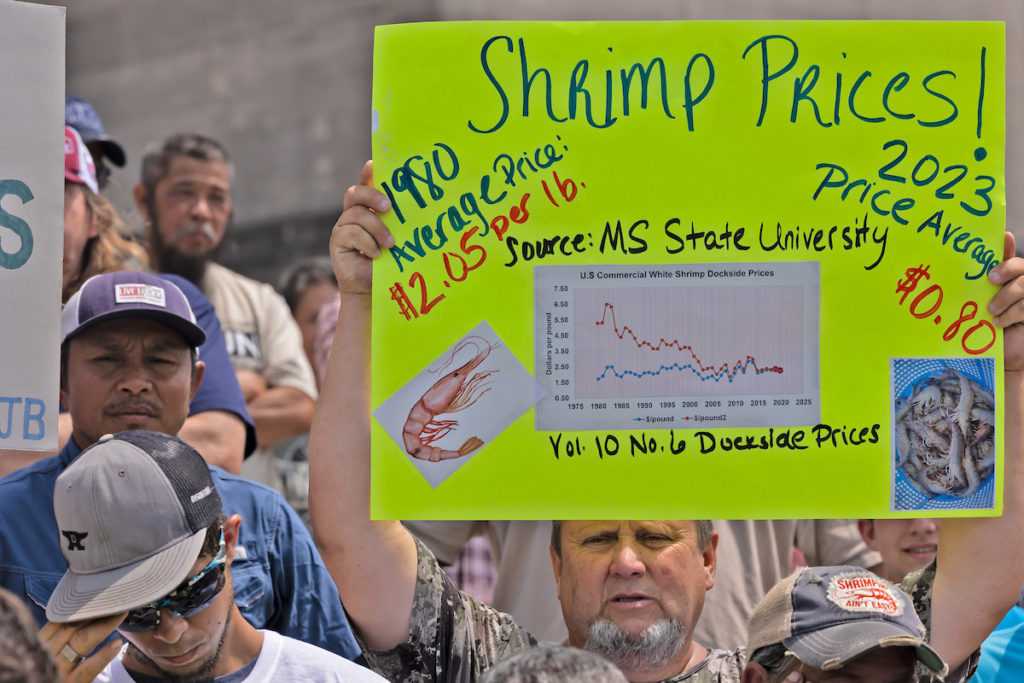

As Cooper made his remarks, the crowd held up handmade signs urging lawmakers to act. One shrimper held one that showed a graph detailing the falling prices. Another stressed “Family Tradition” while saying “no” to imports. One sign simply read, “We’re dying.”

Homemade signs at a rally by members of the shrimping industry on May 12 called on lawmakers to take action on imports. One sign read, “We’re dying,” while another read, “We Feed America,” a nod to Louisiana providing 25 percent of U.S. market demand for shrimp. Photo by ©Julie Dermansky/Independent Reporter

Cooper, a third-generation shrimper, later told the PBS NewsHour that it’s clear “the flood of imports is driving the industry into extinction.”

Louisiana accounts for about 25 percent of the overall U.S. market demand for shrimp, according to the Louisiana Shrimpers Association. After Alaska, Louisiana fishermen bring in the second largest volume of seafood in the country.

But importers, these shrimpers say, are bringing in more shrimp to the U.S. than what’s consumed each year — and that’s driving down the price for Louisiana shrimp.

While many of the fishermen are asking lawmakers for a ban on imports, Cooper acknowledged that was a big ask. “We know we are not going to get a total ban on imports, but just give us a cap and control it to where we can make a living,” he said.

Workers process wild-caught Louisiana shrimp, which are selling for some of the lowest prices the shrimp industry has ever seen due to massive amounts of shrimp being imported from overseas. Photo by Gulf Seafood News

Shrimpers say they now face some of the lowest prices they have ever seen due to large amounts of shrimp being imported from Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Ecuador.

Rodney Oleander has been a shrimper for 45 years. He parked his shrimp boat to drive two hours from the coast to attend the rally. He carried a sign that read, “Shrimpers Lives Matter,” and called on lawmakers to do more to support the industry.

“People are fed up. They’ve been chewed up, spit up and stepped on,” Oleander said. “I’m gonna fight with y’all. I’m not a quitter.”

“We need immediate action now, not down the road.”Louisiana lawmakers are currently considering several bills aimed at protecting the seafood industry. One does request that the federal government ban the import of shrimp and crawfish from outside the U.S. Another asks that the Louisiana’s health department and the USDA expand testing of imported shrimp products. The same bill also urges Congress to support laws requiring labeling of country of origin when those products are sold at restaurants.

Shrimpers believe the federal government has to take a stronger role in saving the industry.

“We need immediate action now, not down the road,” shrimper Kindra Arnesen said at the rally. “These people have been in office for years and years, come to our meetings, and make us believe in empty promises that never come to fruition. We have had enough.”

Kindra Arnesen, flanked by fellow fishermen, speaks at a rally on the steps of the Louisiana State Capitol. She called out lawmakers for “broken promises” and urged them to help the struggling industry. Photo by ©Julie Dermansky/Independent Reporter

In 2019, the Louisiana legislature passed a law requiring restaurants in the state to label imported seafood, specifically shrimp and crawfish. Shrimping advocates say it lacked teeth — with little enforcement, low fines — and many ignored the rule.

Back at the rally, only a handful of lawmakers spoke to the crowd. One of them was Rep. Ryan Bourriaque, a Republican lawmaker from coastal Southwest Louisiana near Lake Charles.

“The economics are simple. When you flood the markets, you know what’s going to happen,” he said. “We’re here to say we do hear you. Hold us accountable.

Rocky Ditcharo, a shrimp processor from Plaquemines Parish who spoke at the rally, said workers weren’t looking for handouts, just “a little bit of help.”

“We don’t have much time. Another year we’ll be dead. DOA,” he said.

A way of life in peril

Shrimp have been harvested commercially in Louisiana since the 1800s. This little crustacean is the backbone of one of the most productive fisheries in the continental United States and central to the culture, heritage and independent livelihoods of many Louisiana families for generations. One out of every 70 jobs in Louisiana is related to the seafood industry.

A commercial shrimp boat with nets extended trawls the waters off the Louisiana coast. It is followed by seabirds looking for an easy meal. The shrimping industry employs 15,000 people and is a vital part of the state’s $2.4 billion seafood industry. Photo by Gulf Seafood News

But shrimpers on the Louisiana coast have faced troubled waters in recent years. State agency officials have warned of heavy economic and cultural impacts to the region if no action is taken to address the effects of climate change. For Cooper, the price of shrimp has been barely high enough to justify trawling.

A week after the rally, he’s back home casting his net but coming up nearly empty. On a good day, he catches 1,500 pounds of shrimp and works around the clock. Now, he pulls in only a third of that amount and works fewer hours.

“At 50 cents a pound, you can’t make it at that price. I worked till 4 in the morning, and I couldn’t find anything. I ended up stopping. I’m going to be in the hole for last night,” Cooper said from the dock in Venice, Louisiana.

WATCH: Native communities in Louisiana fight to save their land from rising seas

Cooper, who has been a shrimper since he was 15, said while many of his “boot brothers” wouldn’t have considered leaving their livelihoods in the past, they are faced with a new reality.

“Last year was almost a breaking point with the prices lower than we ever seen it,” Cooper said. “When that’s your way of life, and that’s what you’re accustomed to, it’s kind of hard to give that up,” adding that he’s concerned for the small and independent businesses.

A Louisiana shrimper holds up a sign highlighting falling dockside shrimp prices at a May 12 rally at the Louisiana State Capitol. Photo by ©Julie Dermansky/Independent Reporter

Shrimpers on Louisiana’s working waterways have always carried the pride of self-reliance and adaptation to adversity on their shrimp boats. But an influx of imported shrimp from Southeast Asia, rising fuel prices, several traumatic hurricane seasons and the largest marine oil spill in American history have all pushed the trade toward a breaking point.

Dean Blanchard was once one of the largest shrimp suppliers in the country, headquartered on the barrier island of Grand Isle in the Mississippi River Delta.

After five generations, he’s seen the family business slow to a crawl. Sales at Dean Blanchard Seafood have dramatically dropped from $40 million to $12 million annually. His workforce has been depleted from 100 workers to seven.

“We’ve all come to the realization that it’s the imports that is killing this industry. I mean, we’re losing processors, we’re losing docks, we’re losing boats,” he said. “Everybody can see that it’s not just one segment of the industry that’s doing better than the other. They are all doing bad.”

“The mood right now is that we’ve got a culture and a way of life that’s coming to an end.”In past shrimp seasons, Blanchard said the bayou was like a boat parade with horns blowing to signal the bountiful catches. Now it’s grown quiet, and many fear it is nearing the end of a cherished way of life for many Louisiana shrimpers.

“The mood right now is that we’ve got a culture and a way of life that’s coming to an end,” Blanchard said in his Cajun accent. “I got a lot of boats tied up, never left, never even went shrimping this year because they’re scared they won’t be able to cover the expense. You got people losing their houses. I mean, it just makes me cry.”

Blanchard said the federal government should treat the fishing industry like it does farmers, by offering subsidies during tough times.

“Fishermen are salt of the earth people, and for some reason nobody wants to help us. We don’t want no more than a farmer,” Blanchard said. “We are ‘farmers of the sea,’ and we ought to be on the same playing field as them.”

Dean Blanchard works in September 2021 at his seafood processing plant, which has been significantly impacted by overseas imports. It suffered more than a million dollars in damages in due to Hurricane Ida. Photo by Gulf Seafood News.

Statewide shrimp landings, a measure of shrimp production tracked by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, are down by nearly 50 percent over the last two decades, from 147.4 million pounds in 2000 to 74.06 million pounds in 2021.

Meanwhile, imports have skyrocketed. In recent years, the U.S. has become the largest global seafood importer by value.

In 1980, the U.S. imported 250 million pounds of shrimp that were sold at an average of $10 per pound. Last year, the total number of imports was 2 billion pounds, and the price dropped to $4.30 per pound.

“When import prices drop, domestic prices drop in order to compete,” said Peyton Cagle, a marine fisheries biologist at the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Shrimpers also warn that if homegrown shrimp disappears, consumers will pay a higher price in other ways.

The Louisiana Shrimp Association, in particular, has decried additional concerns like cheap labor and government subsidies from overseas countries that allow them to mass produce and export seafood products at a lower price than wild-caught Louisiana shrimp.

“Everybody in this country ought to be alarmed at what they are eating.”A 2019 WVUE-TV investigation, citing data from the Government Accountability Office, reported that more than 12 percent of shrimp samples from overseas contained unsafe residues from antibiotics and other drugs. Farmers may use drugs like antibiotics to keep fish alive in harsher conditions in confined aquaculture areas. The GAO said the misuse of these drugs could lead to unsafe levels in seafood that can cause allergic reactions or even cancer.

Shrimpers like Blanchard say more testing from the Food and Drug Administration is needed because of the threat to consumer health from “tainted shrimp.” These longstanding concerns were supported by the GAO’s 2017 report that found the FDA tests about 2 percent of the total seafood imported annually. The agency has said a lack of resources limits their ability to conduct more inspections.

Cooper said there’s a risk of people eating shrimp that contain antibiotics, steroids and other drugs that could lead to antibiotic resistance.

“Everybody in this country ought to be alarmed at what they are eating — and that’s what we want everybody to know,” he said.

Many shrimpers are keeping their boats docked after prices for their catches have dropped to record lows. The spring brown shrimp season in Louisiana opened in May and runs through July. Photo by Gulf Seafood News.

Cooper is doubtful the current proposed legislation will do much to answer the age-old question of why shrimpers are paid so little for their catches, which garner higher markups at market.

“We’ve been hollering about the same issues, and yet here we are, now to a point where we are about to break, and nobody still wants to step up,” Cooper said. “We got some legislation now, but there’s no meat to them bills. It won’t make any big changes.”

In the past, a strike has helped adjust stagnant domestic seafood prices, but now Cooper says a similar labor action would likely worsen matters. He predicted shrimpers could lose or have trouble regaining market share, given the current state of the industry in Louisiana.

“We’ve got to look at the big picture. [Louisiana shrimpers are] playing on the world market, and you playing for market shares,” Cooper said.

Once overseas shrimpers drive the prices down, run Louisiana shrimpers out and take control of the market, he said, “then you don’t know what the price is going to be.”

After weathering hurricanes that have destroyed entire coastal communities — not to mention the day-to-day conditions of living and working on the water — many shrimpers wonder if it’s the economic winds that will sink their boats for good.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eVmLyvu8yyZqWnpZ7Aqq3NmmSsoKKeurGx0axkmqqVYsSwvtGinJ1lmaK9sL7TrGSwoZyherS1zaRkraCVonqnu9FmnqinlA%3D%3D